Black Mesa (1,739 m - 5,705 feet)

United States of America (Colorado, New Mexico, and Oklahoma)

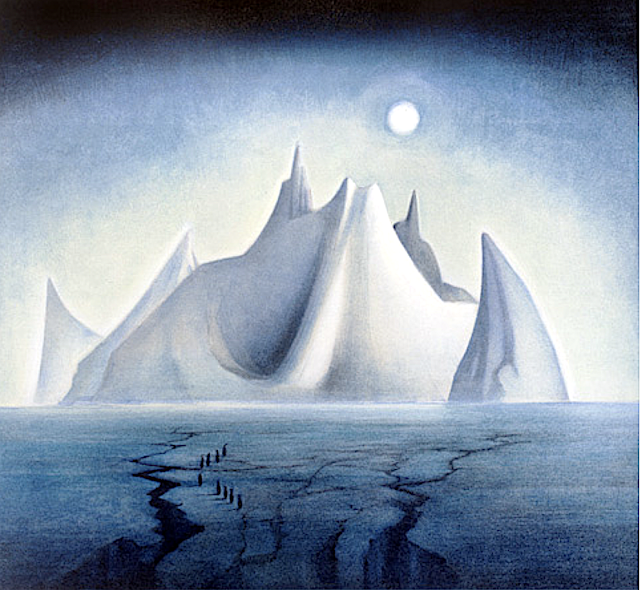

In Near Abiquiu, New Mexico, 1931 Oil on canvas, 0.6 x 91.4 cm, Georgia O' Keeffe Museum

The painter

Georgia O’Keeffe is one of the most significant and intriguing artists of the twentieth century, known internationally for her boldly innovative art. Her distinct flowers, dramatic cityscapes, glowing landscapes, and images of bones against the stark desert sky are iconic and original contributions to American Modernism.

Born on November 15, 1887, the second of seven children, Georgia Totto O’Keeffe grew up on a farm near Sun Prairie, Wisconsin. She studied at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1905-1906 and the Art Students League in New York in 1907-1908. Under the direction of William Merritt Chase, F. Luis Mora, and Kenyon Cox she learned the techniques of traditional realist painting. The direction of her artistic practice shifted dramatically in 1912 when she studied the revolutionary ideas of Arthur Wesley Dow. Dow’s emphasis on composition and design offered O’Keeffe an alternative to realism. She experimented for two years, while she taught art in South Carolina and west Texas. Seeking to find a personal visual language through which she could express her feelings and ideas, she began a series of abstract charcoal drawings in 1915 that represented a radical break with tradition and made O’Keeffe one of the very first American artists to practice pure abstraction. O’Keeffe mailed some of these highly abstract drawings to a friend in New York City, who showed them to Alfred Stieglitz. An art dealer and internationally known photographer, he was the first to exhibit her work in 1916. He would eventually become O’Keeffe’s husband.

In the summer of 1929, O’Keeffe made the first of many trips to northern New Mexico. The stark landscape, distinct indigenous art, and unique regional style of adobe architecture inspired a new direction in O’Keeffe’s artwork. For the next two decades she spent part of most years living and working in New Mexico . She made the state her permanent home in 1949, three years after Stieglitz’s death. O’Keeffe’s New Mexico paintings coincided with a growing interest in regional scenes by American Modernists seeking a distinctive view of America. Her simplified and refined representations of this region express a deep personal response to the high desert terrain.

In the 1950s, O’Keeffe began to travel internationally. She created paintings that evoked a sense of the spectacular places she visited, including the mountain peaks of Peru and Japan’s Mount Fuji. At the age of seventy-three she embarked on a new series focused on the clouds in the sky and the rivers below.

Suffering from macular degeneration and discouraged by her failing eyesight, O’Keeffe painted her last unassisted oil painting in 1972. But O’Keeffe’s will to create did not diminish with her eyesight. In 1977, at age ninety, she observed, “I can see what I want to paint. The thing that makes you want to create is still there.”

Late in life, and almost blind, she enlisted the help of several assistants to enable her to again create art. In these works she returned to favorite visual motifs from her memory and vivid imagination.

Georgia O’Keeffe died in Santa Fe, on March 6, 1986, at the age of 98.

The mountain

Black Mesa (1,739 m - 5,705 feet) is a mesa in the U.S. states of

Colorado, New Mexico, and Oklahoma. It extends from Mesa de Maya,

Colorado southeasterly 28 miles (45 km) along the north bank of the

Cimarron River, crossing the northeast corner of New Mexico to end at

the confluence of the Cimarron River and Carrizo Creek near Kenton in

the Oklahoma panhandle. Its highest elevation is in Colorado. The

highest point of Black Mesa within New Mexico is 1,597 m - 5,239 feet.

The plateau that formed at the top of the mesa has been known as a

"geological wonder" of North America. There is abundant wildlife in this

shortgrass prairie environment, including mountain lions, butterflies,

and the Texas horned lizard.

The plateau has been home to Plains Indians.

In the late-nineteenth and early twentieth century the area was a

hideout for outlaws such as William Coe and Black Jack Ketchum. The

outlaws built a fort known as the Robbers' Roost. The stone fort housed a

blacksmith shop, gun ports, and a piano. The present-day Oklahoma

Panhandle area, which was then considered a no man's land, lacked law

enforcement agencies and hence the outlaws found it safe to hide in the

region. However, as new settlers arrived in the area for copper and coal

mining and also for cattle ranching activities by grazing cattle in the

mesa region, law enforcement became more effective, and the outlaws

were brought under control.

___________________________________________

2021 - Wandering Vertexes...

by Francis Rousseau